Well, I just announced that I was starting a new Books section, so I figure I ought to post a book review. But, I'm going to cheat a little on this first one - I'm going to combine two previous posts, with a little bit of editing, and adding only a paragraph's worth of new content.

The book is the classic, Darwin's The Origin of Species. Long before I picked up the book, I already had a pretty good understanding of evolution - better than most laymen, I'd wager. So I didn't start reading Origin of Species to try to learn anything about the theory. Rather, it was more to do with my interest in history, particularly my interest in the history of science and technology. And it doesn't disappoint.

Okay, let's get the background out of the way, first. Origin of Species was written by Charles Darwin, and was originally published in 1859, with the full title, On the Origin of Species By Means of Natural Selection, or, the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. It's not that Darwin was the first to propose some type of theory of evolution and common descent, but Origin of Species really was the book that presented the evidence in such a way, and proposed a plausible mechanism, that the theory really came to be accepted.

Reading this book changed my perception of Darwin. The story you're always presented with about Darwin is this naturalist who went on a voyage on the Beagle to observe plants and animals, had an epiphany at the Galapagos islands, and came up with this theory of evolution. While this is true to a certain extent, and Darwin was a very keen observer, Origin of Species had more than just his observations from the Beagle and some interesting ideas to explain it. He actually performed experiments to test his ideas. Let me give a couple examples.

In one of the chapters on geographical distribution, Darwin discusses how certain plants might spread from one pond to the other. In addition to trying to think up plausible means, he then goes on to test how plausible they might be. Consider this passage, discussing the possibility of seeds sticking to water fowl and being transported from pond to pond in that way:

I do not believe that botanists are aware how charged the mud of ponds is with seeds: I have tried several little experiments, but will here give only the most striking case: I took in February three table-spoonfuls of mud from three different points, beneath water, on the edge of a little pond; this mud when dry weighed only 6 3/4 ounces; I kept it covered up in my study for six months, pulling up and counting each plant as it grew; the plants were of many kinds, and were altogether 537 in number; and yet the viscid mud was all contained in a breakfast cup!

Later in the same chapter, Darwin discusses inhabitants of oceanic islands, and the problem of how certain animals could have come to live on them. I'll just let Darwin speak for himself on this one:

Almost all oceanic islands, even the most isolated and smallest, are inhabited by land-shells, generally by endemic species, but sometimes by species found elsewhere. Dr. Aug. A. Gould has given several interesting cases in regard to the land-shells of the islands of the Pacific. Now it is notorious that land-shells are very easily killed by salt; their eggs, at least such as I have tried, sink in sea-water and are killed by it. Yet there must be, on my view, some unknown, but highly efficient means for their transportal. Would the just-hatched young occasionally crawl on and adhere to the feet of birds roosting on the ground, and thus get transported? It occurred to me that land-shells, when hybernating and having a membranous diaphragm over the mouth of the shell, might be floated in chinks of drifted timber across moderately wide arms of the sea. And I found that several species did in this state withstand uninjured an immersion in sea-water during seven days: one of these shells was the Helix pomatia, and after it had again hybernated I put it in sea-water for twenty days, and it perfectly recovered. As this species has a thick calcareous operculum, I removed it, and when it had formed a new membranous one, I immersed it for fourteen days in sea-water, and it recovered and crawled away: but more experiments are wanted on this head.

It's this practical approach from Darwin that impressed me. He didn't just sit around trying to come up with just-so stories - when he came to a question, he'd go and get his hands dirty doing real experiments.

Part of what I find just so fascinating is how Darwin came up with all this without any knowledge of genetics. Even though Gregor Mendel was performing his pea plant experiments around the same time that Darwin wrote Origin of Species, it appears that Darwin wasn't really aware of Mendel's work. In fact, it wasn't until the early 1900's that the scientific community recognized the importance of Mendel's experiments. And it wasn't until the 1940's and 50's that people finally understood what DNA was and how it controlled heredity. Obviously, people in the 1800's knew that offspring bore some resemblance to their parents, but nobody knew how exactly this happened, or what it was that caused offspring to have variations. So Darwin was kind of left groping around in the dark, and all throughout the book, he's reduced to explaining concepts while admitting that he doesn't truly understand the mechanisms responible. From a modern viewpoint, understanding genetics, it almost makes you wish you could travel back and explain it to Darwin. It would have made things so much easier for him.

So knowing that Darwin was ignorant of genetics, and knowing that our knowledge of the geologic record was even less complete then than it is now, it's interesting to see the insights Darwin had that lead him to formulate the theory. For me, when I think of evolution, I think of fossils. Yeah, I know there are multiple other lines of evidence, but growing up, that was the main line of evidence that convinced me that evolution actually happened. But Darwin only briefly discusses fossils in two chapters of the book. The rest of Origin of Species is about what he observed in the world around him - how there seem to be clusters of similar species, the difficulties of distinguishing between true species and merely varieties of the same species, the geographical distribution of species, etc.

It's also interesting how Darwin determined that variation and natural selection were the mechanisms responsible for evolution. Consider one of Darwin's contemporaries, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. Lamarck came up with the idea of "Use and Disuse," that animals could affect their own bodies through their actions, and that they could then pass on these acquired traits to their offspring. The classic example of this is a giraffe stretching its neck to reach higher leaves, and it's offspring thus having a longer neck because of it. Thanks to genetics, we now know this is a false view. To be fair, Darwin didn't rule this out entirely in Origin of Species, but he concluded that it must have been secondary to variation and natural selection. And one of the best examples he used to demonstrate this was ants - all the variation evident in workers, even though it's the queen, who isn't directly exposed to the same pressures as the workers, that lays the eggs and is responsible for reproduction.

I also find it fascinating to read Darwin comparing evolution to special creation - to think, that creationism was the dominant scientific theory of the time. What I find especially fascinating, is to think how people integrated this into the knowledge of an ancient earth. Darwin fequently cited Charles Lyell in Orign of Species (Charles Lyell was one of the early popularisers of uniformitarianism, and helped promote the idea of the Earth being truly ancient), and in his chapters on the geological record, Darwin discussed some of the different geological periods. And concerning fossils appearing in the geological record, Darwin tells of how people proposed that those species were created during those periods. Just imagine that - seeing all the evidence for an ancient earth, and thinking that different species had been specially created throughout the history of the earth. I suppose that without a better explanation, and by building on their previous concepts, that it wasn't such a bad idea for the time, but it certainly does seem an odd idea now.

I've read other places that evolution, through Origin of Species, was one of the last major scientific theories that was first presented to the world in a book intended for a lay audience. It wasn't presented in a peer reviewed journal; it wasn't full of technical jargon or equations; it was a book published by a regular publisher and sold through normal venues. It was easy to understand (considering the subject matter), and became a best seller. Now we need science writers to translate for us lay people, so we're always a few steps removed from the real science. It's hard to imagine any new major theories being presented the same way evolution was in Origin of Species.

Another thing I wanted to discuss from Origin of Species is how it made me appreciate how much we know now. Let me explain this a bit - right now, there's a lot we don't know about a lot of things in the universe, and it kind of fills you with a longing to know the answers, even though you know you won't survive long enough to learn them. Like life on other planets - I would love to travel to other solar systems and see how complex life has developed on them, what strategies and structures have evolved in an environment completely isolated from our own, but I know that that's something I'll never know. Now, consider Darwin's condition in relation to his theory, having the limited evidence that he did. In the final chapter of Origin, Darwin wrote, "Numerous existing doubtful forms could be named which are probably varieties; but who will pretend that in future ages so many fossil links will be discovered, that naturalists will be able to decide, on the common view, whether or not these doubtful forms are varieties?" We are those "future ages!" Granted, our knowledge of the fossil record is still far from perfect, but we've discovered so many things since Darwin's time. For example, we now have a pretty good idea how whales evolved, how the first tetrapods went from water to land, how birds evolved from dinosaurs, and so many other things that Darwin could only dream of. So, while I'll still long to know the things I can't, I can at least be grateful for the things we know now, that were the longings of people in the past.

There's one last note I wanted to add, in relation to this edition in particular - the footnotes were wonderful. They're all throughout the text, explaining new things we've learned since Darwin's time, adding supplemental information in a few places, and correcting him in others. I haven't seen any other reprints of Origin of Species to compare this one to, so I don't know if other reprints might have even better footnotes, but I'd definitely consider it worthwhile to get an edition that has modern footnotes. I'm currently reading Voyage of the Beagle. It's a very handsome reprint, and I'm enjoying it immensely, but it doesn't have any modern footnotes, and I find myself constantly looking things up to see if Darwin was right or wrong on certain issues, or even to figure out what exactly he's referring to, when the terms he uses to describe a plant or animal are no longer in common use.

I'd recommend this book to anyone with a good understanding of evolution who's interested in the history of the theory, but not necessarily to those people who don't undertand evolution, yet. For one thing, Darwin gets a few things wrong. For another, being written in a style 150 years old, it's not the easiest thing for a modern reader to understand. And finally, genetics is such a huge component of evolution, that a good introduction to evolution should include genetics in its explanation.

When will there be an aircraft in every garage? In a word - never. Okay, never's a long time, so perhaps I shouldn't be making such a sweeping statement, but I really don't think that it will happen anytime soon.

When will there be an aircraft in every garage? In a word - never. Okay, never's a long time, so perhaps I shouldn't be making such a sweeping statement, but I really don't think that it will happen anytime soon. First, a quick announcement. I've decided to add a new section to this blog,

First, a quick announcement. I've decided to add a new section to this blog,  I only have a very small update for today. Way back when I had my co-op during college, I figured out a way to fold a pretty good

I only have a very small update for today. Way back when I had my co-op during college, I figured out a way to fold a pretty good  Well, today's Columbus Day, so I thought I'd write a little entry about it. (Actually, I'd planned on writing it a year ago for Columbus Day, but didn't get around to it in time.)

Well, today's Columbus Day, so I thought I'd write a little entry about it. (Actually, I'd planned on writing it a year ago for Columbus Day, but didn't get around to it in time.) The single most popular page on this site is my

The single most popular page on this site is my  This past weekend, my family and I went down to the

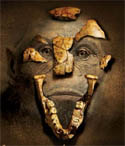

This past weekend, my family and I went down to the  One final note - I really wanted to get some type of coffee cup or shot glass as a souvenir, but just about everything in the gift shop that had to do with Lucy had the same logo on it. And to be honest, I don't particularly like the logo, especially the way it looked printed out small on a mug. If they had just had a picture of the fossil itself, I would have bought one. So instead, I bought a copy of Carl Zimmer's book,

One final note - I really wanted to get some type of coffee cup or shot glass as a souvenir, but just about everything in the gift shop that had to do with Lucy had the same logo on it. And to be honest, I don't particularly like the logo, especially the way it looked printed out small on a mug. If they had just had a picture of the fossil itself, I would have bought one. So instead, I bought a copy of Carl Zimmer's book,